Caregiver Statistics: Work and Caregiving

Definitions

A caregiver—sometimes called an informal caregiver—is an unpaid individual (for example, a spouse, partner, family member, friend, or neighbor) involved in assisting others with activities of daily living and/or medical tasks. Formal caregivers are paid care providers providing care in one’s home or in a care setting (day care, residential facility, long-term care facility). For the purposes of the present fact sheet, displayed statistics generally refer to caregivers of adults.

The figures below reflect variations in the definitions and criteria used in each cited source. For example, the age of care recipients or relationship of caregiver to care recipient may differ from study to study.

Juggling Work and Caregiving

- More than 1 in 6 Americans working full-time or part-time report assisting with the care of an elderly or disabled family member, relative, or friend. Caregivers working at least 15 hours per week indicated that this assistance significantly affected their work life. [Gallup-Healthways. (2011). Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index.]

- American caregivers are a diverse population with between 13% and 22% of workers juggling caregiving and being employed. 22% of caregiving workers are middle-aged and 13% are aged between 18 and 29. [Gallup-Healthways. (2011). Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index.]

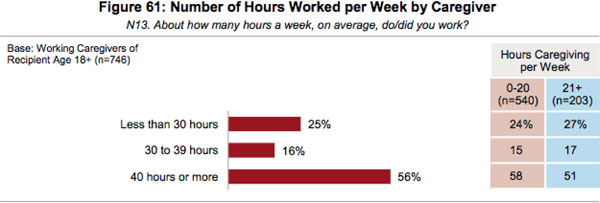

- More than half of employed caregivers work full-time (56%), 16 percent work between 30 and 39 hours, and 25 percent work fewer than 30 hours a week. On average, employed caregivers work 34.7 hours a week.

[National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S.]

Impact on Working Caregivers

- 70% of working caregivers suffer work-related difficulties due to their dual roles. Many caregivers feel they have no choice about taking on caregiving responsibilities (49%). This sense of obligation is even higher in caregivers that provide 21 or more hours of care per week (59%) and live-in caregivers (64%). 60% of caregivers in 2015 were employed at one point while also caregiving. [National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S.]

- Employed caregivers work on average 34.7 hours a week. 56% work full-time, 16% work 30-39 hours/week, and 25% work fewer than 30 hours/week. [National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S.]

- 69% of working caregivers caring for a family member or friend report having to rearrange their work schedule, decrease their hours, or take an unpaid leave in order to meet their caregiving responsibilities. [AARP Public Policy Institute. (2011). Valuing the Invaluable: 2011 Update– The Economic Value of Family Caregiving in 2009.]

- Caregivers who care for a person with emotional or mental health issues are more likely to make work accommodations (77% vs. 67% of those caring for someone with no emotional or mental health issues). [National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2009). Caregiving in the U.S.]

- 6 out of 10 (61%) caregivers experience at least one change in their employment due to caregiving such as cutting back work hours, taking a leave of absence, receiving a warning about performance/attendance, among others. 49% arrive to their place of work late/leave early/take time off, 15% take a leave of absence, 14% reduce their hours/take a demotion, 7% receive a warning about performance/attendance, 5% turn down a promotion, 4% choose early retirement, 3% lose job benefits, and 6% give up working entirely. [National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S.]

- Work is affected even more with co-residence (27%), high burden (73%), primary caregivers (66%), and caregivers involving medical/nursing tasks (70%). [National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S.]

- Caregivers suffer loss of wages, health insurance and other job benefits, retirement savings or investment, and Social Security benefits–losses that hold serious consequences for the “career caregiver.” In 2007, 37% of caregivers quit their jobs or reduced their work hours to care for someone aged 50+. [AARP Public Policy Institute. (2008). Valuing the Invaluable: The Economic Value of Family Caregiving.]

- 39% of caregivers leave their job to have more time to care for a loved one. 34% leave because their work does not provide flexible hours. [National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S.]

- 17% of caregivers of people diagnosed with dementia quit their jobs either before or after assuming caregiving responsibilities. 54% arrive to their place of work late or leave early, 15% take a leave of absence, and 9% quit their jobs in order to continue providing care. [Alzheimer’s Association. (2015). 2015 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures.]

- 10 million caregivers aged 50+ who care for their parents lose an estimated $3 trillion in wages, pensions, retirement funds, and benefits. The total costs are higher for women, who lose an estimated $324,044 due to caregiving, compared to men at $283,716. Lost wages for women who leave the work force early because of caregiving responsibilities totals $142,693. [MetLife Mature Market Group, National Alliance for Caregiving, and the University of Pittsburgh Institute on Aging. (2010). The MetLife Study of Working Caregivers and Employer Health Costs: Double Jeopardy for Baby Boomers Caring for their Parents.]

Impact on Working Female Caregivers

- Working female caregivers may suffer a particularly high level of economic hardship due to caregiving. Female caregivers are more likely than males to make alternate work arrangements: taking a less demanding job (16% females vs. 6% males), giving up work entirely (12% females vs. 3% males), and losing job-related benefits (7% females vs. 3% males). [National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2009). Caregiving in the U.S.]

- Single females caring for their elderly parents are 2.5 times more likely than non-caregivers to live in poverty in old age. [Donato, K. & Wakabayashi, C. (2005). Women Caregivers are More Likely to Face Poverty.]

- Employed caregivers are less willing than non-caregivers to risk taking time off from work; 50% seek an additional job and 33% seek a job to cover caregiving costs. [AARP Public Policy Institute. (2011). Valuing the Invaluable: 2011 Update– The Economic Value of Family Caregiving in 2009.]

Annual Income

- The lower the income and education a person has, the more likely he or she is a caregiver. Similarly, those with a high school education or less (20%) take on a caregiver role versus 15% of college graduates and 16% of postgraduates. [Gallup-Healthways. (2011). Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Survey: More Than One in Six American Workers Also Act as Caregivers.]

- 47% of caregivers have an annual household income of less than $50,000, with a median income of $54,700. African American and Hispanic caregivers are more likely to have an annual household income below $50,000 (62% and 61% respectively). [National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S.]

Impact on Employers

- Only 56% of caregivers report that their work supervisor is aware of their caregiving responsibilities (76% for higher hour caregivers, 49% for lower hour). [National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S.]

- Only 53% of employers offer flexible work hours/paid sick days, 32% offer paid family leave, 23% offer employee assistance programs, and 22% allow telecommuting regardless of employee caregiving burden. [National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S.]

- Caregiver absenteeism costs the U.S. economy an estimated $25.2 billion in lost productivity (based on the average number of work days missed per working caregiver, assuming $200 in lost productivity per day.) [Gallup-Healthways. (2011). Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Survey: Caregiving Costs U.S. Economy $25.2 Billion in Lost Productivity.]

- 24% of caregivers feel that caring for an aging family member, relative, or friend has an impact on their work performance and keeps them from working more hours. [Gallup-Healthways. (2011). Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Survey: Caregiving Costs U.S. Economy $25.2 Billion in Lost Productivity.]

- About 17% of U.S. full-time workers act as caregivers. They report missing an average of 6.6 workdays per year, which amounts to 126 million missed workdays each year. In 2011, 36% of caregivers missed 1-5 days while 30% reported missing 6 or more days. [Gallup-Healthways. (2011). Gallup-Healthways Wellbeing Survey: More Than One in Six American Workers Also Act as Caregivers.]

- Caregiving has shown to reduce employee work productivity by 18.5% and increase the likelihood of employees leaving the workplace. [Coughlin, J. (2010). Estimating the Impact of Caregiving and Employment on Well-Being: Outcomes & Insights in Health Management.]

- One-third of working caregivers are working professionals and another 12% are in service or management roles. 71% indicate their employer knows about their caregiving status and 28% report their employer is unaware. When surveyed about workplace programs, approximately one-quarter or less stated they have access to employer-sponsored support (e.g. support group discussions, ask-a-nurse type services, financial or legal consultation, and assisted living counselors). [Gallup-Healthways. (2011). Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Survey: Caregiving Costs U.S. Economy $25.2 Billion in Lost Productivity.]

- The cost of informal caregiving in terms of lost productivity to U.S. businesses is $17.1 to $33 billion annually. Costs reflect absenteeism ($5.1 billion), shifts from full-time to part-time work ($4.8 billion), replacing employees ($6.6 billion), and workday adjustments ($6.3 billion). [MetLife Mature Market Group, National Alliance for Caregiving, and the University of Pittsburgh Institute on Aging. (2010). The MetLife Study of Working Caregivers and Employer Health Costs: Double Jeopardy for Baby Boomers Caring for their Parents.]

- Employees with caregiving responsibilities cost their employers an estimated 8%–an additional $13.4 billion per year–more in health care costs than employees without caregiving responsibilities. [MetLife Mature Market Group, National Alliance for Caregiving, and the University of Pittsburgh Institute on Aging. (2010). The MetLife Study of Working Caregivers and Employer Health Costs: Double Jeopardy for Baby Boomers Caring for their Parents.]

Best Practices for Removing Barriers to Equal Employment

- The following six (6) employer practices are recommended:

- Adopt a policy valuing caregiver employees based on job performance rather than holding them to outdated assumptions that they are not committed to their jobs.

- Allow workplace flexibility, which provides alternate work arrangements: flex-time, compressed workweeks (i.e., working 10 hour days), part-time or working fewer hours for part of the year, and telecommuting.

- For hourly employees on more strict schedules, do away with no-fault absenteeism policies that provide termination based on number of tardies or absences no matter the reason.

- Provide education and training to supervisors and managers about having caregivers on the job and what constitutes caregiver discrimination.

- Offer eldercare support, resources, and referral services to caregiver employees. By doing so, employers benefit from better worker retention, improved productivity, lower stress, improved moral and physical health among workers.

- Implement recruitment practices for persons with eldercare responsibilities to target the hiring of skilled caregiver individuals or who are looking to reenter the job market after caring. [Williams, J. C., Devaux, R., Petrac, P., & Feinberg, L. (2012). Protecting Family Caregivers from Employment Discrimination.]

- A 2011 Gallup poll suggests that employers should provide the following:

- An employee assistance plan to promote discussions about emotional distress experienced by the working caregiver;

- Access to health counselors or “ask a nurse” for information on the care receiver’s condition;

- Access to counselors or others to make referrals and give advice about assisted living or nursing homes. [Gallup-Healthways. (2011). Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Survey: Caregiving Costs U.S. Economy $25.2 Billion in Lost Productivity.]

- 2 out of 3 caregivers support additional policy proposals preventing workplace discrimination against employees with caregiving responsibilities. [National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S.]

Family Caregiver Alliance

National Center on Caregiving

(415) 434-3388 | (800) 445-8106

Website: www.caregiver.org

Email: info@caregiver.org

FCA CareNav: https://fca.cacrc.org/login

Services by State: www.caregiver.org/connecting-caregivers/services-by-state/

Family Caregiver Alliance (FCA) seeks to improve the quality of life for caregivers through education, services, research, and advocacy. Through its National Center on Caregiving, FCA offers information on current social, public policy, and caregiving issues and provides assistance in the development of public and private programs for caregivers. For residents of the greater San Francisco Bay Area, FCA provides direct support services for caregivers of those with Alzheimerʼs disease, stroke, traumatic brain injury, Parkinsonʼs, and other debilitating disorders that strike adults.

The present fact sheet was prepared by Family Caregiver Alliance. © 2016 Family Caregiver Alliance. All rights reserved.