HIV-associated Neurocognitive Disorder (HAND)

Since the start of the AIDS epidemic more than three decades ago, doctors, family and friend caregivers, and patients have observed that some people with the disease experience decline in brain function and movement skills, as well as shifts in behavior and mood. This disorder is called HIV-associated Neurocognitive Disorder, or “HAND.” Although advances in antiretroviral therapy from the past two decades have decreased the severity of HAND, symptoms still persist in 30–50% of people living with HIV. For many people, these symptoms continue to affect activities of daily living.

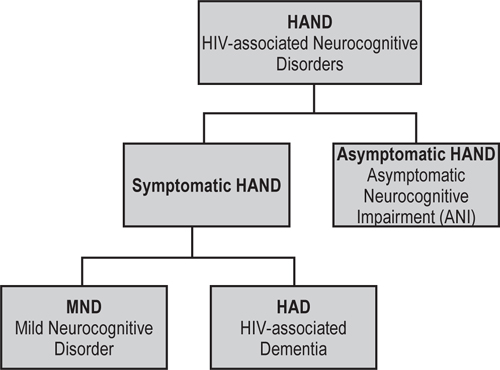

The most severe form of HAND, called HIV-associated Dementia (HAD), now occurs in less than 5% of people who have access to antiretroviral therapy. The more common form of HAND is Mild Neurocognitive Disorder (MND). Symptoms of MND include behavioral changes; difficulty in making decisions; and learning, attention, concentration, and memory difficulties. Some patients develop tremors or loss of coordination. A third form of HAND has been described in research studies: Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment (ANI). Study participants with ANI have impaired performance on neuropsychological tests yet don’t recognize having any symptoms. Early studies suggest that these participants do poorly on tests that evaluate their daily function, suggesting they have real impairment that goes unrecognized. Others note that participants with ANI are more likely to develop symptomatic impairment (e.g. MND) than are participants who test normally on cognitive tests. The following figure summarizes the breakdown of HAND and its various forms.

Risk factors for developing HAND are less clear for people who are taking and adhering to antiretroviral therapy and who have undetectable amounts of HIV in their body fluid (also known as “viral load.”) For those who are not taking these medications, treatment is recommended. It is especially important that patients with detectable viral loads seek care and adhere to medications to achieve an undetectable viral load. Both age and other illnesses appear to increase risk. In untreated patients, a low CD4 count remains a risk factor. CD4 cells or T-helper cells are a type of white blood cell that fights infection.

There is no “typical” course of the ailment. Several groups have described daily fluctuation in abilities. Most of the time, HAND remains relatively mild in patients with suppressed viral load. HAND may be severe or progress rapidly. Some people experience only cognitive disturbances or mood shifts, while others struggle with a combination of mental, motor, and behavior changes. How much these changes disrupt a person’s day-to-day life differs from one individual to the next and from one stage of the disease to another.

Facts

Managing HAND is sometimes difficult because side effects from medications, other HIV infections, nutritional imbalances, depression, and anxiety, as well as the effects of comorbid diseases (e.g. vascular disease and liver impairment) can all contribute to cognitive, behavioral, and mood disturbances.

Because neurological changes often develop gradually, it can be a challenge to determine exactly when isolated incidents or symptoms should be given a diagnosis of HAND. In the era of HIV where most people are on treatment, it is becoming clearer that cognitive impairment is often due to more than one cause.

Before the arrival of combination anti-retroviral therapy (also known as cART and sometimes referred to as HAART) in the second half of the 1990s, dementia, the most severe form of HAND, was a frequent finding in late-stage disease. More recently, experts have estimated that less than 5 percent of people on cART develop HAND, although many more suffer from mild changes that can affect daily living.

Symptoms

Unlike many of the infections associated with HIV and AIDS, HAND has a wide range of possible symptoms, which can vary greatly from one person to the next. The symptoms of HAND fall into three broad categories:

- Cognitive: problems in concentration (difficulty following the thread of a conversation, short attention span, inability to complete routine tasks, trouble finishing a sentence); memory loss (trouble recalling phone numbers, appointments, medication schedules, agreements, or previous conversations); and a generalized slowdown in mental functions (difficulty understanding and responding to questions, loss of sense of humor or wit).

- Motor: poor coordination, weakness in legs, difficulty maintaining balance, tendency to drop things, decline in clarity of handwriting, loss of bladder or bowel control.

- Behavioral: personality changes (increased irritability, apathy toward loved ones or life in general, loss of initiative, withdrawal from social contact); mood swings (depression, excitability, emotional outbursts); impaired judgment (impulsive decision-making, loss of inhibitions); and, on occasion, symptoms of psychosis (hallucinations, paranoia, disorientation, sudden rages).

Cognitive problems are often—although not always—the first to become apparent to a person with HAND and their family members, friends, caregivers, and health care providers. Motor and behavioral changes, if they occur, frequently become evident in later stages of the syndrome.

Diagnosis

Many factors can contribute to the types of symptoms observed with HAND, making diagnosis a complex and challenging task. Depression, other psychiatric disturbances, reactions to medication, and nutritional deficiencies can all lead to similar symptoms. Infections common among people with advanced HIV can also lead to these symptoms, although typically only among those not on cART (e.g. toxoplasmosis, lymphoma, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy [PML], and cryptococcal meningitis).

An accurate diagnosis of HAND, therefore, requires a comprehensive examination that generally includes a mental status test, a brain scan, and sometimes lab tests on the cerebrospinal fluid (the fluid that bathes the brain and spinal cord), which are obtained through a procedure known as a spinal tap or lumbar puncture. A mental status exam can help identify whether a person is suffering from memory loss, difficulties with concentration and other thinking processes, mood swings, and other symptoms. The best diagnosis requires a third party (e.g. friend, partner, or other family member) to corroborate the behavior/memory changes.

Because no single test definitively answers the question of whether someone has HAND, the final diagnosis is made by weighing all the evidence together. Time and repeated measures are helpful in confirming a diagnosis.

Treatment

Although there is no cure for HAND, the single most important treatment is adherence to antiretroviral therapy to maintain a suppressed viral load in the blood. The specific medicines that make up the cART regimen appear to be less important than just being on a regimen. In rare cases, doctors may have to consider how well these medicines get into the central nervous system, and studies are currently underway to determine whether some medications may help symptoms better than others. These new findings, however, should not cloud our understanding that suppression of plasma virus to undetectable or unquantifiable levels in blood appears to be most critical.

Knowing the diagnosis is also sometimes therapeutic, as there is stigma and stress related to these symptoms and how they affect daily activities. These can be addressed with proper diagnosis. Knowing that the illness exists may also prompt compensatory approaches and, ultimately, decrease stress and anxiety.

In addition to treating HAND itself, it is important to find ways to treat the secondary symptoms when possible. Anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, and anti-anxiety drugs can help relieve some of the mental distress people with HAND may experience. However, some of these medications may cause complications when taken along with antiretroviral therapy or other drugs; caution is needed in choosing the best approach. Consultation with an HIV-knowledgeable doctor is recommended.

It is also important that patients engage in their own care to prevent factors that can contribute to cognitive symptoms. This includes aggressive treatment of depression, good health care maintenance to address common comorbidities (e.g. hypertension, lipid abnormalities, liver impairment), avoiding non-prescription drugs and excessive alcohol, working with care providers to assure that the medications taken are all required, and exercise. There is growing evidence that physical exercise is important. Optimally, this can be done while engaging in other activities, since social integration and activities may also be helpful. Keeping engaged with enjoyable activites likely translates into benefits.

Advice for Caregivers

Caring for someone with HAND can be stressful. Part of the difficulty is that caregivers must cope with not just the practical implications of the situation—for example making sure the person remembers to take medications on time—but also with the loved one’s own fears and despair about the deterioration of his or her abilities. Exhaustion, fear, isolation, and grief of the loss of the relationship and partnership that once was, are common for caregivers. The fact that HAND can impact behavior (e.g. apathy, depression) and that many people suffer from HAND but don’t feel they have symptoms, makes caregiving even more challenging.

Encouraging someone to obtain a proper diagnosis is an important first step. Because the loss of control can be terrifying, however, some individuals with HAND may be unwilling to admit they are suffering from cognitive loss. Caregivers should be prepared for possible resistance to seeking help. It is important to remind the patient as gently as possible that there may be ways of addressing and improving the situation once the diagnosis is clarified.

This is also the time to make sure that all important legal documents (visit www.caregiver.org/where-find-my-important-papers), such as advance directives, financial durable powers of attorney, POLST (physician orders for life sustaining treatment) forms, and estate plans have been prepared with the help of a knowledgeable attorney for both the patient and their care partner.

Just as in the early stages of Alzheimer’s or other cognitive disorders, there are steps a caregiver can take to make the situation as manageable as possible. In addition to getting informed about HAND, the available treatments, and working with a competent care team, there are steps one can take in their daily life to maximize function and decrease stress.

One of the primary coping strategies is to keep the home environment familiar. Memory prompts, such as calendars, lists, beepers, and pill boxes, can be helpful in alleviating frustration for both the caregiver and the person living with the condition. Matching the ability of the person to the prompt tools used is key to successful use of these aids. For some patients with more severe impairment or dementia, consider simplifying communication by gaining eye contact before you speak, repeating the names of visitors, and talking slowly and clearly while retaining an adult tone of voice and level of respect. It is often helpful to limit the number of tasks that need to be done at the same time and break down directions into one- or two-step commands.

For caregivers themselves, the demands of coping with a person suffering from cognitive loss—whether related to AIDS or another disorder—can be challenging. Feelings of isolation, depression, guilt, rage, despair, and fear are common. It can be crucial for caregivers to seek help themselves, whether in the form of individual counseling or support groups with others in similar circumstances.

Caregivers must build time in the week to take breaks and recharge. Hiring outside assistance, such as a home health aide, to help care for an individual with HAND (particularly individuals with the advanced form, dementia) can be essential to achieving a degree of balance in life. In addition, social service agencies can provide caregiver consultations, respite for caregivers (a break from care), daycare programs, and other practical support services. Some caregivers feel ashamed that they cannot do everything and are reluctant to access such support, especially if the one who is ill resists. But getting the support you need in order to maintain your ability to carry on with caregiving responsibilities and stay healthy while doing so—even over possible objections—can be a genuine expression of love and concern.

Resources

Family Caregiver Alliance

National Center on Caregiving

(415) 434-3388 | (800) 445-8106

Website: www.caregiver.org

Email: info@caregiver.org

FCA CareNav: https://fca.cacrc.org/login

Services by State: https://www.caregiver.org/connecting-caregivers/services-by-state/

Family Caregiver Alliance (FCA) seeks to improve the quality of life for caregivers through education, services, research and advocacy. Through its National Center on Caregiving, FCA offers information on current social, public policy, and caregiving issues and provides assistance in the development of public and private programs for caregivers, as well as a toll-free call center for family caregivers and professionals nationwide. For San Francisco Bay Area residents, FCA provides direct family support services for caregivers of those with Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, ALS, head injury, Parkinson’s, and other debilitating brain disorders that strike adults.

FCA Fact and Tip Sheets

A listing of all facts and tips is available online at www.caregiver.org/fact-sheets.

Taking Care of YOU: Self-Care for Family Caregivers

Where to Find Your Important Papers

Special Concerns for LGBTQ+ Caregivers

Community Care Options

Other Organizations and Links

Medical Treatment and Research

UCSF Memory and Aging Center

www.memory.ucsf.edu

An international leader in the field of memory disorders and dementia. The center offers comprehensive evaluations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients, conducts research on new therapies and offers support groups for patients, family members and friends.

Neurology Caregiver Corner

wiki.library.ucsf.edu/display/NeurologyCaregiverCorner/Home

Information, Advocacy, and Support: National

AIDS.Gov

https://www.hiv.gov/

Gay Men’s Health Crisis

www.gmhc.org

The Body

www.thebody.com

This website publishes an online magazine and other materials on all aspects of HIV/AIDS, including dementia, and also offers a bulletin board, chat rooms, and additional opportunities to interact with others.

Information, Advocacy, and Support: San Francisco Bay Area

San Francisco AIDS Foundation

www.sfaf.org

UCSF Alliance Health Project

www.ucsf-ahp.org

UCSF 360 Positive Care Center

www.ucsfhealth.org/clinics/hiv_aids_program/index.html

Shanti Project

www.shanti.org

Openhouse

www.openhouse-sf.org

This fact sheet was prepared by Family Caregiver Alliance and updated and reviewed by P. Esmaeili, BS, N. Boissier, LCSW and V. Valcour, MD, PhD., UCSF Memory and Aging Center. © 2015 Family Caregiver Alliance. All rights reserved.